Recently, one of our catalogers was searching for OCLC copy for the DVD of the film The girl with the dragon tattoo. He (very reasonably) typed:

girl with the dragon tattoo

into the title field of Connexion. He got no hits. Why?

Advanced search options

Whether you use them or not, you have probably seen helpful hints or advanced search options detailed in search interfaces. The basic search page on my library’s OPAC has these small words near the bottom:

Search Tips: enter words relating to your topic, use quotes to search phrases: “world wide web”, use + to mark essential terms: +explorer, use * to mark important terms: *internet, use ? to truncate: browser?

These can help narrow or order your search results if you choose to use them, but are unlikely to cause trouble if you forget they exist and just type what makes sense.

For example, if you searched for the book “Because I said so” by its exact title, the quotation marks (which are part of the title) specify that because I said so must be in the title as a phrase (which it is) so that title would still appear in the search results.

For example, if you searched for the book “Because I said so” by its exact title, the quotation marks (which are part of the title) specify that because I said so must be in the title as a phrase (which it is) so that title would still appear in the search results.

If you searched for the book Are you my mother? by its exact title, the question mark would allow truncation of mother, and could return (among other things) the blog Are you my mothership? The desired book would also appear in the search results, so again, no harm done.

Boolean operators

Other advanced search options you’ll often see are boolean operators, most commonly AND, OR and NOT. These options combine search requirements to obtain more precise results:

- A search for dog AND house will return items with both dog and house in them.

- A search for dog OR house will return items with either dog or house (or both) in them.

- A search for dog NOT house will return items with dog in them but not house in them.

In OCLC Connexion, these operators are available as pulldowns you can use to search for combinations of fields, but they also work when just typed into the individual search fields. They are straightforward enough to use, but since they are common English words, it is easy to use them accidentally, particularly when you are copy cataloging (searching for a record for a known title).

For example, a searcher looking for the book War and games might just type into the title field: war and games. This would return not only records for the desired title, but also titles without the word “and”, because they have war AND games in them:

For example, a searcher looking for the book War and games might just type into the title field: war and games. This would return not only records for the desired title, but also titles without the word “and”, because they have war AND games in them:

This is a broader search result than desired, but not too bad.

As another example, consider a searcher looking for records for the book Hit or myth, and typing in a title search: hit or myth. That would return all of the titles that contained hit:

and ALSO all of the titles containing myth:

That set of search results (those that contain hit OR contain myth) is significantly larger than what you’d get for the intended search (for the phrase hit or myth), but at least that title will be somewhere among the results.

A worse example still is accidental use of NOT. Suppose a searcher was looking for a record for the Newbery Medal winner Bud, not Buddy and used the search bud not buddy. That would retrieve all of the titles that contain bud but do not contain buddy. That is, it would retrieve titles like:

A worse example still is accidental use of NOT. Suppose a searcher was looking for a record for the Newbery Medal winner Bud, not Buddy and used the search bud not buddy. That would retrieve all of the titles that contain bud but do not contain buddy. That is, it would retrieve titles like:

but Bud, not Buddy would NOT be among the search results, because it contains the word buddy.

Try this yourself: what do these searches do?

- to be or not to be

- ready or not

Proximity operators

Sneakier than the boolean operators are the proximity operators WITH and NEAR. These allow you to not only specify which words must appear in your records, but also their positions in relation to each other.

WITH or just W means that the words on either side of it must be next to each other, and in the order given. For example, the search girl with the dragon specifies that “girl” must appear before and right next to “the”, so this would return The girl, the dragon, and the wild magic, but not The girl with the dragon tattoo.

NEAR or just N means that the words on either side of it must be next to each other, but may be in either order. For example, the search be near me would return Let me be free and I gotta be me but not Be near me.

Try this one too: what would this search do?

- n or m

For those actually wanting to use proximity operators, not just avoid them, note that you can also add numbers to them to specify a maximum distance between the terms, so the search gone w2 wind would match Gone with the wind.

Quotation marks

You can mostly avoid all of the trouble described above by surrounding parts of your search with quotation marks as appropriate. The searches “bud not buddy” and “girl with the dragon tattoo” will more or less work as you expect.

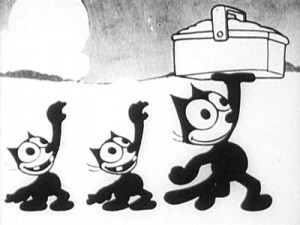

I qualify the statements above because of Connexion’s treatment of stopwords. These are words that are so common that OCLC does not include them specifically in its indexes. For example, if you do a title search for “felix the cat” and look in the title bar, you’ll see that the search has been converted to ti: felix w1 cat. So a quoted search containing stopwords will preserve the spacing between non-stopwords.

I qualify the statements above because of Connexion’s treatment of stopwords. These are words that are so common that OCLC does not include them specifically in its indexes. For example, if you do a title search for “felix the cat” and look in the title bar, you’ll see that the search has been converted to ti: felix w1 cat. So a quoted search containing stopwords will preserve the spacing between non-stopwords.

This is helpful, but not sufficient to give an exact search, as it might allow different words in between the search terms, including ones that aren’t also stopwords. For example, a title search “people of the book” would be converted to people w2 book; that is, it allows at most two words to appear between people and book. That search would return People of the book, but would also return Are women people? A book of rhymes for suffrage times.

So use quotation marks liberally, and check out OCLC’s full list of stopwords if you suspect they are tripping you up. One last thing to watch out for though, where even quotation marks won’t help you:

Articles at the beginning of a title

When a title begins with an article, in a MARC record we specify a number of non-filing characters to specify how the title should be sorted. That is, we want The cardturner to sort between Carcasonne and Care and feeding of sprites, not down with the other titles that start with The, so we tell it to skip the first 4 characters and sort (or file) from there. This has the side effect of telling OCLC where to start indexing, so a title search for “the cardturner” will return no results! You have to search only for cardturner.

When a title begins with an article, in a MARC record we specify a number of non-filing characters to specify how the title should be sorted. That is, we want The cardturner to sort between Carcasonne and Care and feeding of sprites, not down with the other titles that start with The, so we tell it to skip the first 4 characters and sort (or file) from there. This has the side effect of telling OCLC where to start indexing, so a title search for “the cardturner” will return no results! You have to search only for cardturner.

It is easy enough to remember to not include a beginning a, an or the at the beginning of a title we’re searching for; even the OPAC requests that. When things really get tricky is when the titles are in another language. In many languages we can guess that those tiny words at the beginning of the title are articles (La in Spanish, Das in German, etc.) but in some languages, there is no space between the article and the following word. The French title L’amour en miettes would have 2 non-filing characters (so that L’ is skipped). The Arabic title al-Arḍ would have 3 (skipping al-). If you are having trouble finding copy for a title in a foreign language, try skipping the first word entirely.

Anything else?

What trips you up when you’re searching in Connexion? How do you work around it?