“AACR2 is not appropriate for today’s cataloging environment, because it was developed in the age of catalog cards.” I keep hearing this assertion, and always wonder… what is the actual problem?

AACR2’s age is an issue; its chapter division into specific formats, and primarily the formats that existed at the time of its writing (1978, last revised 2005), may not scale as more formats become available. But why the mention of catalog cards? How did they stifle AACR2?

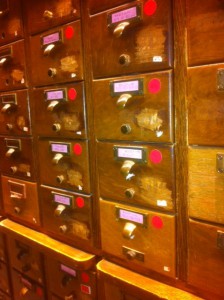

Catalog cards are small, so abbreviations must be used.

One immediately recognizable difference in RDA records is the lack of common AACR2 abbreviations. RDA records spell out pages instead of using p., illustrations instead of ill., and color (or colour) instead of col. Similarly, common Latin abbreviations are expanded into sometimes lengthy phrases; for example, [S.l.] becomes [Place of publication not identified]. These unabbreviated forms are arguably easier for patrons to interpret, but hardly justify the creation of a new cataloging code. With such a straightforward expansion of existing abbreviations, this change is largely a matter of display, similar to the OPAC showing Title: instead of 245.

More problematic are the abbreviations of content from the specific item being cataloged, shortened according to cataloger judgment. For example, the AACR2 rule for recording the publisher’s name says to use the “shortest form in which it can be understood and identified internationally”, a decision that requires some judgment from the cataloger. Different catalogers may look at the same piece, and record the publisher as “Charles Scribner’s Sons”, “C. Scribner’s Sons” or simply “Scribner’s”. Such differences were not a problem on catalog cards where the goal was to identify the publisher; any of the above versions is sufficient to distinguish that book from one published by Houghton, Mifflin and Co. In the OPAC however, such differences make searching by publisher tricky. A publisher search for “Charles Scribner’s Sons” will not retrieve records that use the shorter versions, where a search for “Scribner” will retrieve not only records by the desired publisher, but also some from different publishers, such as “Scribner & Welford”.

In the card catalog, the publisher was not intended to be an access point like author or subject; adding it would have substantially increased the size of the catalog (adding one extra card for each title in the collection!) for relatively little gain. OPACs can easily maintain many more indexes, though their accuracy suffers from inconsistent data. RDA’s rule to transcribe the publisher’s name exactly as it appears on the piece allows the publisher’s name to appear in the catalog as consistently as it does on the cataloged material itself.

Catalog cards have metadata in context.

I recently worked on a project where I extracted metadata from AACR2 (or earlier) MARC records for inclusion in Dublin Core records. While troubleshooting my crosswalk, I looked at individual fields outside of the context of their records (say, a list of all of the titles in the record group), and while doing so, noticed some strange things.

The first oddity that stood out was a group of records whose publisher was recorded as simply “The Survey”. That sounded generic; in what way was that internationally recognizable as a specific publisher? I looked back at the original record, and found that its main entry was “Kentucky Historical Records Survey”. The brief phrase in the publisher name subfield was a reference to the fuller form that already appeared in the main entry. Why waste card space writing it out twice? I checked some other records with that corporate body as a main entry, and found that some listed no publisher at all! Viewed as a whole, such a record is clear, but “The Survey” is a poor publisher access point, particularly if it is also used in records for the West Virginia Historical Records Survey.

A similar situation arises in catalog records for individual volumes of an author’s collected works. Viewed on the context of a full record, the series statement “His collected works” makes sense; it refers to the author mentioned in the record. A series search for that phrase in my local OPAC brought up 22 results (fewer than I expected) from nearly that many authors. It is odd that they appear at all, as those records even have a 490 indicator saying not to trace that series.

In my Dublin Core project, I also noticed that a number of the publication dates were of the format “1942]”. There’s no mystery where this came from. The publication information in the record is in some way questionable, or taken from somewhere other than the chief source, so had a format such as:

[Frankfort : Kentucky Department of Agriculture, 1942]

This specific field is no problem to deal with. The trailing ] on the year can either be stripped for simplicity, or used to record the sketchy nature of the publication date. The leading [ in the location of publication can be used similarly, but what about the publisher’s name? Extracted in the straightforward way, the name of the publisher would be “Kentucky Department of Agriculture” with no indication that it was not taken from the chief source. Again, seeing this field in the context of the full record (as it would be on a catalog card) provides additional information not apparent from the field’s own content. This issue has actually been addressed already for AACR2 records by a change to the ISBD standard, in which such publication information should now be recorded this way:

[Frankfort] : [Kentucky Department of Agriculture], [1942]

though the old way is still common in both legacy and new data.

Is that all?

Catalog cards are small and the physical spaces to store them limited, so AACR2 encourages (often dictates) abbreviation, sometimes resulting in loss of data.

Is that all, though? How else did the card catalog environment shape AACR2 into something not good enough for the current cataloging environment, and how does RDA address this?