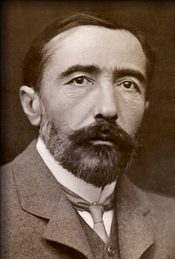

What do Nick Hornby, Joseph Conrad, and J.K. Rowling have in common? Under LC classification, they are a shelf-reading nightmare!

The Problem

This summer, our Circulation department is doing a large shelf-reading project in the stacks, and invited the rest of the library to join in the fun. Yesterday I got to shelf-read around PR 6000 (English literature–1900-1960–Individual authors). I didn’t have any major problems as I worked through Joseph Conrad, then Noël Coward, and A.J. Cronin through what I thought was the end of the C’s, when suddenly there was half a shelf of books in random order, including a bunch of Joseph Conrad and Noël Coward. I know shelves get out of order, but what the heck happened there?

LC Classification

In the literature sections of Library of Congress Classification, authors are assigned classification numbers based on a combination of their country, time period, name and how much they have written (or had written about them). They may even get different amounts of them: William Shakespeare has over 300 class numbers all to himself (PR2750 – PR3112) where Charles Dickens only gets 49 (PR4550 – PR4598). Many authors only get one number (Joanna Baillie has PR4056) and most modern authors only get one cutter number (Zilpha Keatley Snyder has PS3569.N93).

In some sections where the author only gets one cutter, the number already includes information about the first letter of the last name, so the cutter starts with the second letter of the last name. So an LC classification for The Egypt Game might look like:

| PS | American literature |

| 3569 | Individual authors–1961-2000, last name starting with S |

| .N93 | Cutter starting with the N in Snyder, built with cutter table |

| E39 | Title cutter, also built with cutter table |

| 1967 | Publication date |

So what’s the problem?

In the LC classification, the whole number directly following the initial class letter can also have a decimal point followed by more numbers before you get to any cutters. For example, materials on the history of motion pictures are classed under PN1993.5, so you might see call numbers like PN1993.5.I84 (history of motion pictures in Indonesia). So just looking at a random call number, the character following the decimal point can be either a number or a letter, and you may have difficulty distinguishing between a zero and the letter O. This can make a major difference in where the book is shelved!

For example, Joseph’s Conrad’s autobiography with the call number PR6005.O4 Z46 1983 (with a letter O) would be shelved with his journals and memoirs, between PR6005.O4 Z459 (dictionaries, indexes of his work) and PR6005.O4 Z48 (his collected letters). If you misread the letter O as a zero, it would be shelved after ALL of the PR6005 (English authors, 1900-1960, whose names started with C) so it would go after Henry Cust (PR6005.U773) and before Ella D’Arcy (PR6007.A522), nowhere near the other books related to Joseph Conrad.

This is precisely the confusion that comes up with many contemporary authors having a last name with second letter O. They are assigned a single cutter starting with O, which may be mistaken for a zero. For example:

| Joseph Conrad | PR6005.O4 |

| Nick Hornby | PR6058.O689 |

| J. K. Rowling | PR6068.O93 |

What to do?

In part, this is a problem of font choice and labeling. If a clear font were chosen for labeling, the two characters would be more easily distinguishable, particularly in a call number that contained both. I realize that this is difficult to maintain over time with changing label printers, and that opinions may differ on what is both readable and attractive; I personally have a soft spot in my heart for DPCustomMono2. When a call number is printed as a column of its parts, care should be taken to put cutters starting with the letter O on a separate line than the main class number.

Just from looking in my own catalog though, I cannot blame all of this on labeling and shelving issues. Many cutters starting with the letter O are printed on the book labels as zeros because they are in the catalog that way! In many cases, the call number is correct in the bibliographic record, but the letter O somehow became a zero when it was copied to the holdings record. Some of this could be avoided by taking care to copy-and-paste identifiers like call numbers when possible, as small changes in them can make a big difference.

BUT I also cannot blame this entirely on local catalogers. Some examples I found in my catalog were wrong in our local bibliographic record because they are wrong in the OCLC record! One that I found was an LC record, and the call number is like that in LC’s catalog! How many hundreds of people copied those same crazy call numbers into their local catalog, and now have their books shelved who-knows-where? Ugh…

I checked a small section of our catalog and found 143 potential instances of this problem. These are materials whose call number starts with P, and which somewhere includes “.0”. This should capture anything in P that has a cutter starting with the letter O (for whatever reason) but was transcribed somewhere as just a decimal number. In Voyager, I used an SQL query like:

SELECT MFHD_MASTER.DISPLAY_CALL_NO, BIB_TEXT.BIB_ID, BIB_TEXT.TITLE FROM (BIB_TEXT INNER JOIN BIB_MFHD ON BIB_TEXT.BIB_ID = BIB_MFHD.BIB_ID) INNER JOIN MFHD_MASTER ON BIB_MFHD.MFHD_ID = MFHD_MASTER.MFHD_ID WHERE MFHD_MASTER.CALL_NO_TYPE = ‘0’ AND MFHD_MASTER.DISPLAY_CALL_NO Like ‘P*.0*’;

There may be some false hits in those results, but all the ones I’ve checked so far have been problems.

It may seem picky to hunt these down in the catalog; it probably is. The books that were out of order in the section I was shelf-reading were actually cataloged correctly, but just shelved in the wrong place. The few catalog problems that I’ve checked on the shelf have labels that look (basically) like they should, and are shelved in the correct place contextually, so they probably don’t even need to be re-labeled. I think the problem comes when you use call numbers programmatically, such as extracting all of your Joseph Conrad books by call number range, or generating a sorted shelf-list for inventory. With so many titles in our collection, patrons may never make it to the physical shelves to browse through them; at that point, things that aren’t indexed correctly in the catalog are as good as lost.

Questions

Have you checked your catalog for problems like these? Did you find any?

Have you noticed any other systematic problems with call numbers or shelving? (Do one and the letter I have the same problem?)

Also check ones and L’s. From the old typewritten catalog cards, lowercase L was used for the number one.

Good idea!

I just searched for “.l” (dot ell) among our call numbers and did find some. At a glance, it looks like some of them should be ones (“no.l6”) and others should be capital L’s. Nice!

Do you know of any reason a call number would legitimately have a pipe character (I) in it? I found one of those as well, and am not sure if it should be a one, or an L, or an I, or has some deeper meaning.

I could be wrong, but I don’t think I’ve ever encountered a call number that has a decimal subdivision starting with a zero. If this is the case, and I’m really racking my brains to come up with a counter example, then it would seem that LC doesn’t allow this to happen specifically to circumvent this very issue.

If that’s the case then, then it would probably help to train shelvers with this information (a decimel will never start with a zero, so if it looks like a zero, either it’s an ‘O’ or it is a zero and that’s a mistake).

Of course, if it’s in the catalog as a zero, that’s a bigger problem because that means that the ILS is going to file it as a decimal starting with a zero.

I could be wrong though… am I wrong?

I thought about this yesterday and went on a hunt. There are legitimate call numbers with decimal subdivision starting with zero!

For example, under the Biography and memoirs of Louis XVI:

DC137.05 Flight

DC137.07 Imprisonment

DC137.08 Trial and death

DC137.09 Other

Darn! That would’ve made things so much easier. Alright new idea, no books about Louis XVI, ever. Or just class them under Marie Antoinette 😉

Hi – v interesting. A long time ago, in a galaxy far away, I used to do cataloguing using pre-printed input forms, which were collected at the end of the day to be processed by a data inputting team. I still remember the rules for handwritten numerals …

Zero must include an oblique stroke; 1 should have a serif at the top; 2 should have no straight lines; 3 must have a horizontal top stroke; 4must be closed where the diagonal meets the upright; the ‘loops’ in 6 and 9 must be fully closed; 7 must be crossed; and woe betide you if your 5 looked like an S.

For your collection, here’s another subdivision starting with 0 (zero) …

http://lccn.loc.gov/65002393

That one is under PR2750, which I’m struggling with right now cos I don’t work in a library any more :-((( Is there a guide anywhere which explains how the subdivisions in PR2750 are created?

If only those conventions had been followed more closely, we wouldn’t be in this mess. 🙂

That’s another great example! I just checked the PR schedule, and it says that PR2750 is for original quartos and facsimiles and reprints of Shakespeare’s works. Cutter .A is for original editions; cutter .B is for facsimiles and reprints, and cutter .C is for collected reprints.

.C is arranged chronologically, but .A and .B are arranged and numbered like PR2801-2873 (Shakespeare’s works), which starts with the plays:

PR2801 – All’s well that ends well

PR2802 – Antony and Cleopatra

…

PR 2807 – Hamlet

…

So the record you point to (with call number PR2750 .B07 1964) is for a facsimile of Hamlet, published in 1964.

Thanks Zem, that’s really useful. I can now get on with cataloguing my personal library :-))

Coming back to sloppy handwriting, master Will Shakespeare was a prime culprit: his ‘u’ must have looked very like an ‘a’, resulting in phrases like ‘unsallied lily’ (Love’s Labour’s Lost) and ‘too too sallied flesh’ (Hamlet Q2). The ‘solid flesh’ in the 1623 Folio is presumably an attempt by some early and unacknowledged ‘editor’ to make sense of the phrase.

PS all my books in PR2750 are in cutter B. Regrettably, I don’t have a single one that qualifies for cutter A.